Intelligence (Psychology)

I have my own thoughts on intelligence in my Intelligence note. These are notes taken from https://nobaproject.com/textbooks/paul-wehr-new-textbook/modules/intelligence when I took PSYCH101.

Definition of Intelligence

The question of what constitutes human intelligence is one of the oldest inquiries in psychology. When we talk about intelligence we typically mean intellectual ability. This broadly encompasses the ability to learn, remember and use new information, to solve problems and to adapt to novel situations.

Book Smart vs. Street Smart

Fluid vs Crystallized Intelligence

Younger people rely on fluid intelligence (capacity to adapt to new situations and use trial and error to quickly figure out solutions).

By contrast, older people tend to rely on crystallized intelligence (use superior store of knowledge to solve problems).

- There’s some interesting thoughts about this, and what Coding Interviews are about, and what companies are looking for?

Ideally, leetcode = fluid intelligence, thinking on the spot. And when they ask technical questions like how you would build a VR headset, you could use crystallized intelligence.

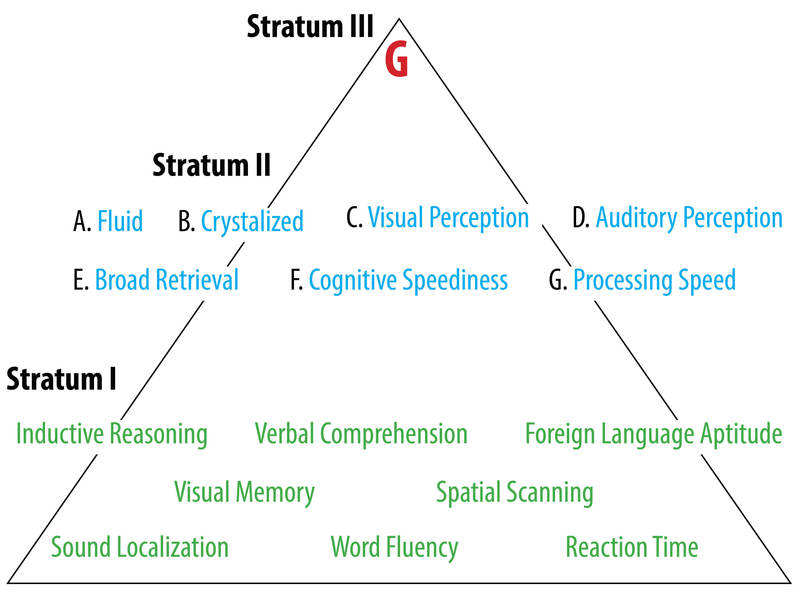

Carroll divided intelligence into three levels, or strata, descending from the most abstract down to the most specific.

Fluid and crystallized intelligence both show up on stratum II of Carroll’s model.

8 Common Types of Intelligences

- logic-math, 2) visual-spatial, 3) music-rhythm, 4) verbal-linguistic, 5) bodily-kinesthetic, 6) interpersonal, 7) intrapersonal, and 8) naturalistic

Difference in Intelligence between Men and Women

This is super interesting.

Even today women make up between 3% and 15% of all faculty in math-intensive fields at the 50 top universities. This phenomenon could be explained in many ways:

- it might be the result of inequalities in the educational system

- it might be due to differences in socialization wherein young girls are encouraged to develop other interests

- it might be the result of that women are—on average—responsible for a larger portion of childcare obligations and therefore make different types of professional decisions, or it might be due to innate differences between these groups, to name just a few possibilities.

The possibility of innate differences is the most controversial because many people see it as either the product of or the foundation for sexism. In today’s political landscape it is easy to see that asking certain questions such as “are men smarter than women?” would be inflammatory. In a comprehensive review of research on intellectual abilities and sex Ceci and colleagues (2009) argue against the hypothesis that biological and genetic differences account for much of the sex differences in intellectual ability. Instead, they believe that a complex web of influences ranging from societal expectations to test taking strategies to individual interests account for many of the sex differences found in math and similar intellectual abilities.

A more interesting question, and perhaps a more sensitive one, might be to inquire in which ways men and women might differ in intellectual ability, if at all. That is, researchers should not seek to prove that one group or another is better but might examine the ways that they might differ and offer explanations for any differences that are found. Researchers have investigated sex differences in intellectual ability. In a review of the research literature Halpern (1997) found that women appear, on average, superior to men on measures of fine motor skill, acquired knowledge, reading comprehension, decoding non-verbal expression, and generally have higher grades in school. Men, by contrast, appear, on average, superior to women on measures of fluid reasoning related to math and science, perceptual tasks that involve moving objects, and tasks that require transformations in working memory such as mental rotations of physical spaces. Halpern also notes that men are disproportionately represented on the low end of cognitive functioning including in intellectual disability , dyslexia, and attention deficit disorders (Halpern, 1997)..

Other researchers have examined various explanatory hypotheses for why sex differences in intellectual ability occur. Some studies have provided mixed evidence for genetic factors while others point to evidence for social factors (Neisser, et al, 1996; Nisbett, et al., 2012). One interesting phenomenon that has received research scrutiny is the idea of stereotype threat. Stereotype threat is the idea that mental access to a particular stereotype can have real-world impact on a member of the stereotyped group. In one study (Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1999), for example, women who were informed that women tend to fare poorly on math exams just before taking a math test actually performed worse relative to a control group who did not hear the stereotype. Research on stereotype has yielded mixed results and we are currently uncertain about exactly how and when this effect might occur. One possible antidote to stereotype threat, at least in the case of women, is to make a self-affirmation (such as listing positive personal qualities) before the threat occurs. In one study, for instance, Martens and her colleagues (2006) had women write about personal qualities that they valued before taking a math test. The affirmation largely erased the effect of stereotype by improving math scores for women relative to a control group but similar affirmations had little effect for men (Martens, Johns, Greenberg, & Schimel, 2006).

These types of controversies compel many lay people to wonder if there might be a problem with intelligence measures. It is natural to wonder if they are somehow biased against certain groups. Psychologists typically answer such questions by pointing out that bias in the testing sense of the word is different than how people use the word in everyday speech. Common use of bias denotes a prejudice based on group membership. Scientific bias, on the other hand, is related to the psychometric properties of the test such as validity and reliability. Validity is the idea that an assessment measures what it claims to measure and that it can predict future behaviors or performance. To this end, intelligence tests are not biased because they are fairly accurate measures and predictors. There are, however, real biases, prejudices, and inequalities in the social world that might benefit some advantaged group while hindering some disadvantaged others.