Rust

Shaheer says that this would be an interesting language for me to learn due to my interests in Accelerated Computing.

I will learn Rust if it has cool applications in robotics.

https://www.tangramvision.com/blog/why-rust-for-robots

Matician (now matic) is coded entirely in rust. Don’t need to worry about memory safety. It’s great. Never see a segmentation fault again.

https://www.thecodedmessage.com/posts/best-programming-language/ https://www.thecodedmessage.com/tags/rust-vs-c++/

Key properties of Rust

The last expression in a function is its return value. You can use return to get C-like behaviour, but you don’t have to.

fn return_a_number() -> u32 {

let x = 42;

x+17

}

fn also_return() -> u32 {

let x = 42;

return x+17;

}Variables in Rust are, by default, immutable:

fn main() {

let x = 42; // NB: Rust infers type "i32" for x.

x = 17; // compile-time error!

}Very important

immutability by default is a good thing because it helps the compiler to reason about whether or not a race condition may exist. No writes = no Data Race

In C, this could potentially be a data race if another thread writes to my_pointer :

if ( my_pointer != NULL ) {

int size = my_pointer->length; // Segmentation fault occurs!

/* ... */

}Ownership

C++ supports memory management via RAII, and Rust does the same, but Rust does so at compile-time with guarantees, through ownership.

Rules of ownership in Rust

There are 3 simple rules for ownership:

- Every value has a variable that is its owner.

- There can be only one owner at a time.

- When the owner goes out of scope, the value is dropped.

fn main() {

let x = Vec<u32>::new(); // similar to the std::vector type in C++

let y = x;

dbg!(x, y); // x has been moved, this is a compiler error!

}You can look at the following example

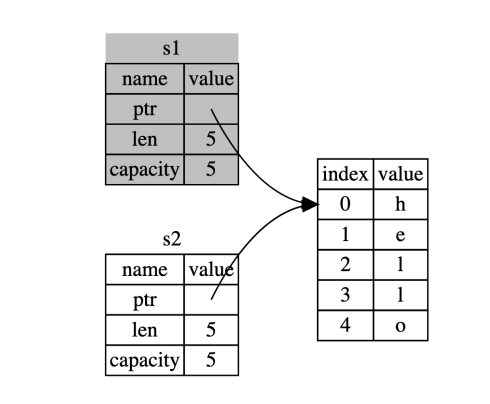

let s1 = String::from("Hello");

let s2 = s1; // ownership moved to s2

println!("{}", s1); // ❌ error: s1 was movedUnder the hood, this is what is happening

However, note for simpler types, they are just copied because it is cheap and moving would be cumbersome (but this is the exception, not the rule)

let x = 5;

let y = x;

dbg!(x, y); // Works as you would expect!What’s interesting about rust is that we can also leverage move semantics when returning a value from a function, and vice versa.

This works

fn make_string() -> String {

let s = String::from("hello");

return s;

}

fn main() {

let s1 = make_string();

println!("{}", s1);

}And vice-versa

fn use_string(s: String) {

println!("{}", s);

// String is no longer in scope - dropped

}

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("world");

use_string( s1 ); // Transfers ownership to the function being called

// Can’t use s1 anymore!

}- In this example, we cannot access

s1after callinguse_string, since the ownership has been transferred to that function! We’ll need to introduce the concept of borrowing if we want to keep usings1afterwards

Can these things happen in Rust?

- Memory leak (fail to deallocate memory)—does not happen in Rust because the memory will always be deallocated when its owner goes out of scope.

- Double-free — does not happen in Rust because deallocation happens when the owner goes out of scope and there can only be one owner.

- Use-after-free—does not happen in Rust because a reference that is no longer valid results in a compile time error.

- Accessing uninitialized memory—caught by the compiler.

- Stack values going out of scope when a function ends—the compiler will require this be moved or copied before it goes out of scope if it is still needed.

The tradeoff that this requires more of the programmer at compile time, but I’d argue this is a really good thing.

Borrowing

Ownership is about “who frees it,” borrowing is about “who can touch it”.

For the concept of borrowing in rust, we use references & (you can think of it as a read-only view, unless you specify mut)

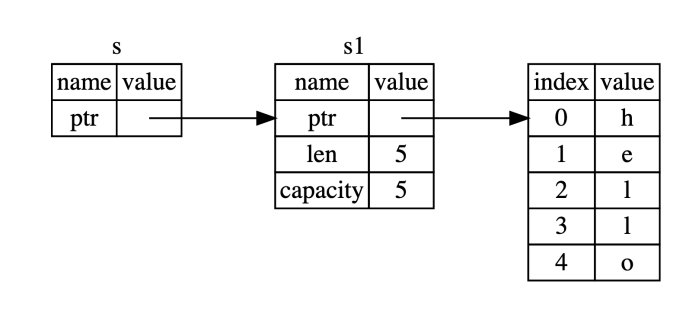

Consider this example:

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let len = calculate_length(&s1);

println!("The length of ’{}’ is {}.", s1, len);

}

fn calculate_length(s: &String) -> usize {

s.len()

}Under the hood, this is what happens

By default, references are immutable: if you borrow something, you cannot change it, even if the underlying data is mutable. However, we can explicitly define mutable references with the &mut:

fn main() {

let mut s1 = String::from("hello");

let len = calculate_length(&mut s1);

println!("The length of ’{}’ is {}.", s1, len);

}

fn calculate_length(s: &mut String) -> usize {

s.len()

}- in this case, we actually need

let mut s1(i.e. defined as mutable), otherwise we cannot create a mutable reference

Mutable reference restrictions

Mutable references come with some big restrictions:

- While a mutable reference exists, the owner can’t change the data, and

- There can be only one mutable reference at a time, and while there is, there can be no immutable references

This is to prevent race conditions.

References also cannot outlive their underlying objects.

WON’T COMPILE

fn main() {

let reference_to_nothing = dangle();

}

fn dangle() -> &String {

let s = String::from("hello");

&s // returning a thing that no longer exists upon return

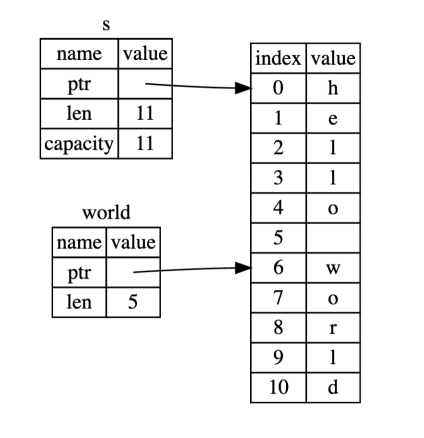

}We also have the concept of slices

fn main() {

let s = String::from("hello world");

let hello = &s[0..5];

}

Concurrency

This is the exciting part.

Threads

Rust uses threads for concurrency, with a model that resembles the create/join semantics of the POSIX Thread.

Spawning a thread

use std::thread;

use std::time::Duration;

fn main() {

let handle = thread::spawn(|| {

for i in 1..10 {

println!("hi number {} from the spawned thread!", i);

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(1));

}

});

for i in 1..5 {

println!("hi number {} from the main thread!", i);

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(1));

}

handle.join().unwrap();

}What is this

||?In Rust,

|| { ... }is closure syntax — basically “an anonymous function”.

- The two pipes

||are where closure parameters go

Some examples:

|| 42

// a closure that takes no args and returns 42

|x| x + 1

// takes 1 arg

|x, y| x + y

// takes 2 args

move || { /* ... */ }

// zero args, but `move` forces captured variables to be moved into the closure

What does

movedo?Move on a closure means: capture the variables you use by value (ownership) instead of by reference.

Let’s have threads communicate with each other

use std::sync::mpsc;

use std::thread;

fn main() {

let (tx, rx) = mpsc::channel();

thread::spawn(move || {

let val = String::from("hi");

tx.send(val).unwrap();

});

let received = rx.recv().unwrap();

println!("Got: {}", received);

}Traits in Rust are a lot like interfaces.

pub trait FinalGrade {

fn final_grade(&self) -> f32;

}

impl FinalGrade for Enrolled_Student {

fn final_grade(&self) -> f32 {

// Calculation of average according to syllabus rules goes here

}

}We have mutexes in rust

use std::sync::Mutex;

fn main() {

let m = Mutex::new(5);

{

let mut num = m.lock().unwrap();

*num = 6;

}

println!("m = {:?}", m);

}However, it seems like a mutex is not really amenable to our model of single ownership, since multiple threads need to access this mutex.

2 types of smart pointers introduced:

Box<T>Rc<T>

use std::sync::Arc;

use std::sync::atomic::{AtomicBool, Ordering};

fn main() {

let quit = Arc::new(Mutex::new(false));

let handler_quit = Arc::clone(&quit);

ctrlc::set_handler(move || {

let mut b = handler_quit.lock().unwrap();

*b = true;

}).expect("Error setting Ctrl-C handler");

while !(*quit.lock().unwrap()) {

// Do things

}

}- Mutex used to protect boolean that’s used concurrently (once in main, once in handler)

Then, we can talk about lifetimes

This WON’T compile

fn main() {

let string1 = String::from("abcd");

let string2 = "xyz";

let result = longest(string1.as_str(), string2);

println!("The longest string is {}", result);

}

fn longest(x: &str, y: &str) -> &str {

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}- The issue is that it can’t figure out whether the return value is borrowing

xory, so it’s not sure how long those strings live

We can fix this with a lifetime annotation

fn longest<’a>(x: &’a str, y: &’a str) -> &’a str {

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}- You need the

'since lifetime names always start with an apostrophe in rust

Important

Memory that’s kept around forever that is no longer useful is fundamentally very much like a memory leak, even if it is still possible to deallocate it in a hypothetical sense.

To do anything that qualifies as unsafe, you declare a block as unsafe.

unsafe {

do_unsafe_thing();

}Inside an unsafe block, you can do the following things that you are not normally allowed to do:

- Call an unsafe function/method

- Access or modify a mutable static variable

- Implement an unsafe trait

- Access the fields of a union

- Dereference a raw pointer

You can do something like accessing raw pointers

let mut num = 5;

let r1 = &num as *const i32;

let r2 = &mut num as *mut i32;

unsafe {

println!("r1 is: {}", *r1);

println!("r2 is: {}", *r2);

}Common pitfalls

- Overuse of static lifetime to band-aid ownership issues

- Using clone() much more than needed to try to avoid borrow-checker complexity

- Underestimating the overhead of array indexing rather than use of an iterator

- Unbuffered I/O

- Expensive operations like resize() on a vector

- Assuming everything will always go right and just using unwrap() with no handling of errors

- Vibe coding: the LLM’s code may not be fully correct or optimal!

Async

use futures::executor::block_on;

async fn hello_world() {

println!("hello");

}

fn main() {

let future = hello_world();

block_on(future);

}Libcurl

use std::io::{stdout, Write};

use curl::easy::Easy;

// Write the contents of rust-lang.org to stdout

let mut easy = Easy::new();

easy.url("https://www.rust-lang.org/").unwrap();

easy.write_function(|data| { // callback function

stdout().write_all(data).unwrap();

Ok(data.len())

}).unwrap();

easy.perform().unwrap();But we probs want to use the async version, so you can consider the following program:

const URLS:[&str; 4] = [

"https://www.microsoft.com",

"https://www.yahoo.com",

"https://www.wikipedia.org",

"https://slashdot.org" ];

use curl::Error;

use curl::easy::{Easy2, Handler, WriteError};

use curl::multi::{Easy2Handle, Multi};

use std::time::Duration;

use std::io::{stdout, Write};

5

struct Collector(Vec<u8>);

impl Handler for Collector {

fn write(&mut self, data: &[u8]) -> Result<usize, WriteError> {

self.0.extend_from_slice(data);

stdout().write_all(data).unwrap();

Ok(data.len())

}

}

fn init(multi:&Multi, url:&str) -> Result<Easy2Handle<Collector>, Error> {

let mut easy = Easy2::new(Collector(Vec::new()));

easy.url(url)?;

easy.verbose(false)?;

Ok(multi.add2(easy).unwrap())

}

fn main() {

let mut easys : Vec<Easy2Handle<Collector>> = Vec::new();

let mut multi = Multi::new();

multi.pipelining(true, true).unwrap();

for u in URLS.iter() {

easys.push(init(&multi, u).unwrap());

}

while multi.perform().unwrap() > 0 {

// .messages() may have info for us here...

multi.wait(&mut [], Duration::from_secs(30)).unwrap();

}

for eh in easys.drain(..) {

let mut handler_after:Easy2<Collector> = multi.remove2(eh).unwrap();

println!("got response code {}", handler_after.response_code().unwrap());

}

}Thread Pools

use std::collections::VecDeque;

use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex};

use threadpool::ThreadPool;

fn main() {

let pool = ThreadPool::new(8);

let queue = Arc::new(Mutex::new(VecDeque::new()));

println!("main thread has id {}", thread_id::get());

for j in 0 .. 4000 {

queue.lock().unwrap().push_back(j);

}

queue.lock().unwrap().push_back(-1);

for _ in 0 .. 4 {

let queue_in_thread = queue.clone();

pool.execute(move || {

loop {

let mut q = queue_in_thread.lock().unwrap();

if !q.is_empty() {

let val = q.pop_front().unwrap();

if val == -1 {

q.push_back(-1);

println!("Thread {} got the signal to exit.", thread_id::get());

return;

}

println!("Thread {} got: {}!", thread_id::get(), val);

}

}

});

}

pool.join();

}Misc Notes

Using Vec:

let mut v: Vec<i32> = Vec::new();

v.push(10);

v.push(20);match - must cover all cases, else underspecified

? vs. unwrap vs. expect

unwrap()= “I’m sure; crash if I’m wrong.”?= “If it fails, bubble it up to the caller.”

The function sign

vec!vsvec::new()?They’re the same thing for creating an empty vector. vec![] and Vec::new() both produce an empty

Vec<T>with no allocation. It’s purely a style preference.

Dereferencing:

let mut x = 5;

let r = &mut x;

*r += 1;

assert_eq!(x, 6);

unwrap()

- If it’s

Some(x)/Ok(x)→ gives youx - If it’s

None/Err(e)→ panics (crashes) right there

Use it when:

- you proved it can’t fail (invariant), or

- in quick prototypes/tests, or

- you want a loud crash on programmer bug

?

- Works only inside a function/closure that returns a compatible

ResultorOption - If it’s

Some/Ok→ gives you the inner value - If it’s

None/Err→ returns early from the current function (no panic)

Result

Result<T, E> is Rust’s way of handling operations that can fail, without exceptions.

Ok(value)means it worked and you got aTErr(error)means it failed and you got anE

Arc

- Arc = Atomically Reference Counted

- https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/sync/struct.Arc.html

Inside execute, the pool basically does something like:

- take your closure

- store it in a queue (heap memory)

- worker threads pop closures and run them later

If your closure captured a reference to a stack variable, you’d be risking a dangling reference, because by the time a worker thread actually runs the closure, the stack variable you referenced might already be out of scope (moved on / dropped), so the reference would point to invalid memory.

Rust Compile-time constants (no heap, no runtime init)

Use const or static for fixed values.

const N: usize = 8;

static GREETING: &str = "hello";const: inlined everywhere (no fixed address).static: one fixed location in memory.

If you want a “global” string/array/table known at compile time, this is the cleanest.

Interior Mutability

I ran into this while trying to figure out why we were allowed to mutate a &DashMap without providing the mut keyword, i.e.

Non-concurrent version:

fn process_dictionary_builder_line(..., dbl: &mut HashMap<String, i32>, ...)Concurrent version:

fn process_dictionary_builder_line_concurrent(..., dbl: &DashMap<String, i32>, ...)- The

dbldoes not specifymut, yet we can still modify it!

This is because DashMap implements interior mutability - it allows mutation through a shared reference (&DashMap).

DashMap internally:

- Hashes the key to determine which shard

- Acquires the lock for that shard

- Performs the mutation

- Releases the lock

Similar Rust types with interior mutability

Mutex<T> - &Mutex<T>can mutate via .lock()RwLock<T> - &RwLock<T>can mutate via .write()