Some more info found in Programming Memory, actual implementation found in Memory Allocation

Heap (Memory)

A heap is a data structure for managing memory that allows segments of memory to be allocated and freed for reuse at arbitrary times.

Also see Dynamic Partitioning for some very similar ideas from OS class.

Not to be confused with Heap (the data structure).

A wide misconception is that heap allocation is a primitive operation, such as arithmetic or loads and stores to memory. In fact, they are calls to intricate algorithms that manage interesting Data Structures.

CS241E

Let’s see how a heap is implemented.

One of the first problems is fragmentation. In our attempt to eliminate this, we will arrive at an automatic Garbage Collector.

In A6, the simplest heap we implemented allocated one block after the other by increment the heapPointer (which holds the next unused memory location).

- We know how much to increment the heapPointer because we store the size of each block, and the blocks are next to each other

We reserve an additional bit in each block to indicate whether the block is allocated or free for use.

Once blocks are allocated, we can iterate through the list of blocks in the heap until we found one that is large enough and whose bit indicates that it is free.

- However, this is slow, since we need to do a linear search every time until we find a good block

We make allocation more efficient by organizing all the free blocks in the heap into a Linked List (so we only need to search free blocks).

To implement a Linked List of free blocks, we organize a block like this:

Let’s define the following helper functions:

def size(block) = deref(block)

def next(block) = deref(block + 4)

def setSize(block, size) = assignToAddr(block, size)

def setNext(block, next) = assignToAddr(block + 4, next)- #todo I need a reminder on how deref is implemented

At beginning of program, we will initialize the heap composed of 2 blocks:

- (1st block) A dummy block with no usable space, containing only the two words needed for its header.

- This is to ensure that every real block in the heap has some block before it, reducing the number of special cases we need to consider in the implementations of

mallocandfree

- This is to ensure that every real block in the heap has some block before it, reducing the number of special cases we need to consider in the implementations of

- (2nd block) A free block consisting of the entire remainder of the heap

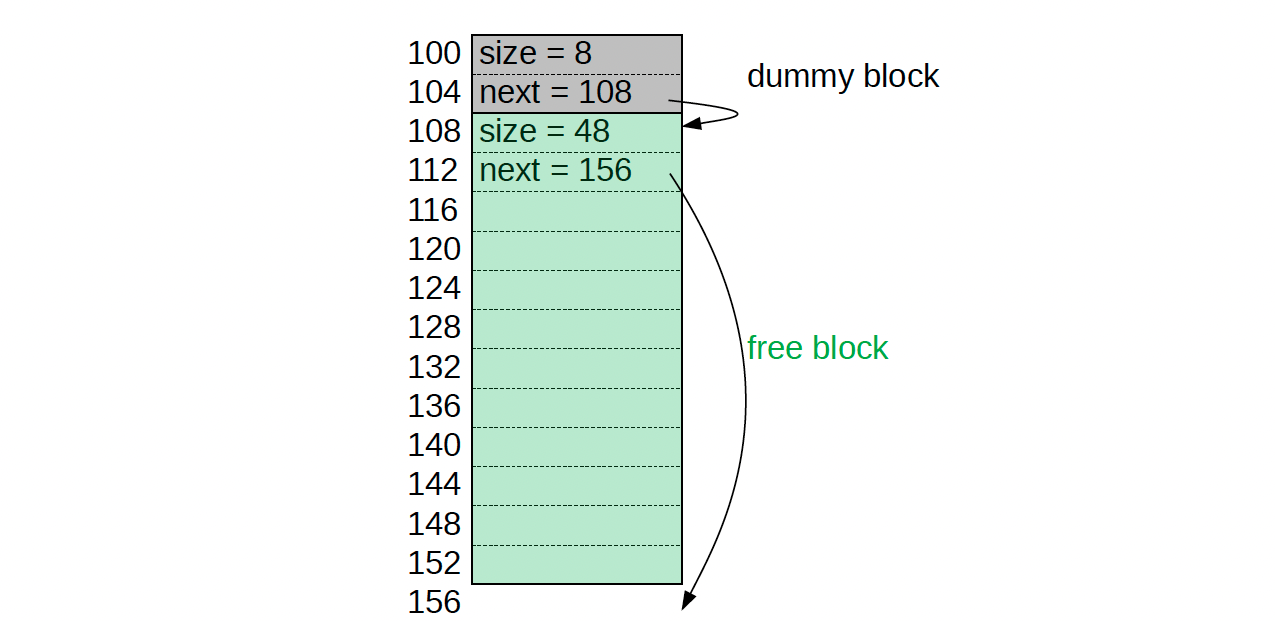

We initialize our heap like this:

def init() = {

val block = heapStart + 8

setSize(heapStart, 8)

setNext(heapStart, block)

setSize(block, heapSize - 8)

setNext(block, heapStart + heapSize)

}For example, if the heap consists of 14 words starting at address 100, the initial state looks like this:

Now that we have initialized our heap, we can allocate a block of wanted bytes of usable space using the following allocation procedure:

def malloc(wanted) = {

def find(previous) = {

val current = next(previous)

if(size(current) < wanted + 8) find(current) // + 8 (4 for size, 4 for next)

else {

if(size(current >= wanted + 16) { // split block

val newBlock = current + wanted + 8

setSize(newBlock, size(current) - (wanted + 8))

setNext(newBlock, next(current))

setSize(current, wanted + 8)

setNext(previous, newBlock)

} else {

// remove current from free list

setNext(previous, next(current))

}

current

}

}

find(heapStart)

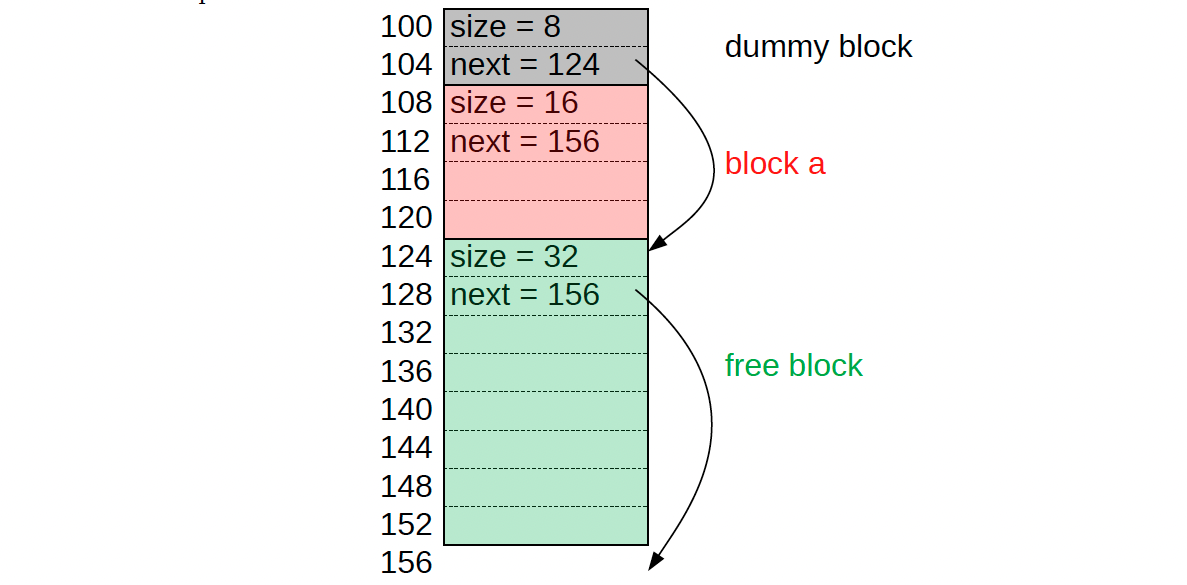

}One neat thing is that we split the block that we find on the free list if it is big enough.

Running the above and calling a = malloc(8) will result in the following heap:

- Notice that the next of block a has not been updated

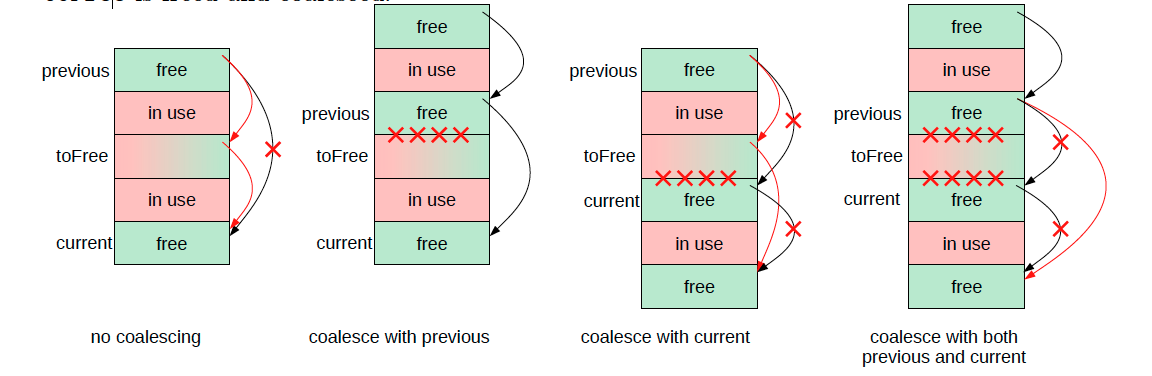

Now, let’s talk about freeing blocks. When a block is used, then it’s not on the linked list of free blocks anymore. So you traverse the linked list of free blocks, until you get to one with an address greater than the one you want to free.

def free(toFree) = {

def find(previous) = {

val current = next(previous)

if(current < toFree) find(current)

else {

val coalesceWithPrevious =

previous + size(previous) == toFree &&

previous > heapStart

val coalesceWithCurrent =

toFree + size(toFree) == current &&

current < heapStart + heapSize

if(!coalesceWithPrevious && !coalesceWithCurrent) {

setNext(toFree, current)

setNext(previous, toFree)

} else if(coalesceWithPrevious && !coalesceWithCurrent) {

setSize(previous, size(previous) + size(toFree))

} else if(!coalesceWithPrevious && coalesceWithCurrent) {

setSize(toFree, size(toFree) + size(current))

setNext(toFree, next(current))

setNext(previous, toFree)

} else { // coalesceWithPrevious && coalesceWithCurrent

setSize(previous, size(previous)+size(toFree)+size(current))

setNext(previous, next(current))

}

}

}

find(heapStart)

}- The first part keeps searching, until you find the right one to free

- The following pair of commands inserts back this block as a freed one

- setNext(previous, toFree)

- setNext(toFree, current)

The implementation above also implements coalescing, which is the process of merging together adjacent free blocks (this process is done when you free a new block). There are 4 cases for coalescing:

Fragmentation and Compaction

However, sometimes, there is the case when there is no coalescing because the free memory blocks are not adjacent to each other. We call this fragmentation.

Fragmentation: When the memory space is split into two small free blocks that cannot be coalesced because they are separated by block b, which is in use.

To reliably avoid fragmentation in all cases, we need to be able to move blocks in memory.

Compaction is the process of moving blocks that are in use together, so they are adjacent in the heap with no fragmented free blocks between them.

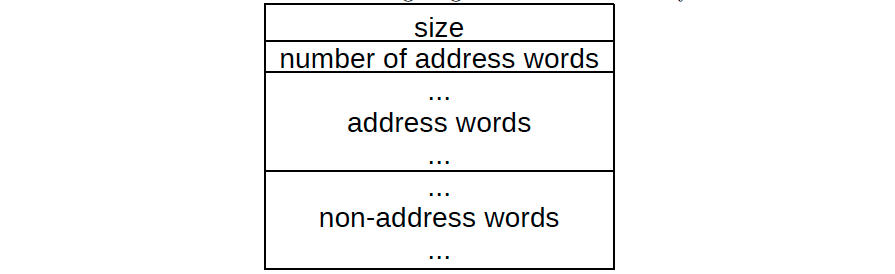

When we move a block, the address of the block changes, therefore, compact requires sound type information so we know which blocks in memory are representing a pointer.

- Therefore, compaction requires sound type information

- We do this is with a convention that within each Chunk, we place all the addresses first, at smaller offsets, and all non-address words afterwards

Reachable

Instead, we design the compaction algorithm to compact all blocks that are reachable by a path of pointers from the stack. If a block is not reachable by such a path, then the executing program can never find its address, and will therefore never access it, so it is safe to consider such a block to be free and reuse its memory.

We implement those through the Garbage Collector.